From the Publisher

On a wet Monday morning, a car runs off the road and kills the author’s father who is on his early morning walk, a short distance from his home. In coming to terms with his father’s senseless and accidental death, the author has written a beautifully crafted, evocative memoir reminiscent of the writings of Jamaica Kincaid and Toni Morrison.

My Father Is No Longer There is nothing less than a meditation on the nature of death, the value of a life, and the nature of art and creativity. It is a manifestation of the author’s quest to get to know his father better than when he was alive.

It is an exploration of family values, the depths of parental love and sacrifice, and the importance of parent-child bonding. My Father Is No Longer There will resonate with all those who have suffered a great loss, be it the death of a loved one, or a parent-child separation.

The Voice

Would you forgive someone who recklessly killed your father? How would you regard someone who took your father’s life, the last in his line, just when he was settling down to enjoying his last few years in retirement? What would you say to the insurance agent who tells you that your father had already lived beyond his useful life and that the road accident that caused his death had simply hastened his demise? That the value of your father’s life was zero; that ‘statistically (your) father was dead long before he was killed’?

These are some of the many questions troubling the victim’s son doubling as narrator in this untypical book by quite possibly any Saint Lucian writer.

My Father Is No Longer There, like author Anderson Reynolds’ 2017 award-winning novel The Stall Keeper, is set mostly in Vieux Fort, ‘a town at the southernmost tip of Saint Lucia’, in the Caribbean. Appropriately, it is the place of birth of the writer, the place where he grew up and was nurtured by his God-fearing, staunch events Day Adventist parents until his mid to late teens (he tendered his resignation from the faith of his parents and family at age 18 years!), the place where he struggled with the very notion of school—until a couple of life-changing developments completely overturned this disposition into a better outlook. Vieux Fort is also the place he returns to after a decade in the USA for an education that circumstances in Saint Lucia could not afford at that time. From the outset, the writer sets the grim tone of what’s to follow: a seventy-plus-year-old man—his father—is out on his routine morning walk along a driveway a short distance from his home and the public hospital (a leftover of US military-occupied Vieux Fort). A reckless young motorist, as if playing God, as if on a mission with a permit to kill—‘And who is this man to be taking lives’ anyway?(pg. 14)—plunges into the septuagenarian father, killing him on the spot.

The riveting narrative portrays the state of mind of the writer/narrator and how he responds: a state of utter disbelief and stubborn denial from the instant the news is conveyed to him till the funeral service and interment and into the days and weeks that follow.

We get insights into the many possible reasons for writing such an account, the most compelling of which being a) to get to know the father better and b) to regain his equilibrium and attain a certain peace that only writing is able to accomplish. ‘My father’s death, the suddenness…the one moment my father was alive…would have to rank high among events that have left a strong and lasting impression upon me…naturally (making it) a candidate for my writing’ (pp.93-94). Or, it is about bringing closure to the father’s business on earth; ‘to validate my father’s life, to say, “Yes, there was a man called St. Brice Reynolds”’ (pg. 95); to immortalize him even?

My Father Is No Longer There, to be truthful, contains many stories, perhaps many books, within one cover. It’s a book, not only about a revered father’s tragic end but also about his life—the character, his journey, the passions, all that depicts the life, the very essence of the man insofar as the writer can claim to have known him up to that point. It’s a book about family (the Reynolds family)—its composition, modus vivendi, their religious and social values, siblings, individual members’ idiosyncrasies, the apparent contrast between the personalities of husband and wife, what glued them together. By all indications, from the children’s perspective, theirs was a life of work, school, work, school…with ‘very little time to play…our home, our house, was like a factory…It was work, work, and more work’ (pp.145ff)…like we were the children of Israel under forced labor…’ (pg. 92).

As if that is not enough, My Father Is No Longer There is also a book about the writer—his infancy (hugely affected adversely by the temporary separation from his mother); growing up in an environment forbidden to merge with his peers and the rest of the community because of religious restrictions; his ‘maladjusted’ childhood; his decade-long sojourn in the USA where he really confronted his demons, coming into a better understanding of self, history and culture, emerging a different, more integrated person (a metamorphosis really).

Unsurprisingly, after his father’s death, more than ever before, with a high level of modern education, he admits that he no longer subscribes to the ‘faith theories’ of the father: ‘My father’s godliness…couldn’t save him from the reckless twenty-four-year-old who took his life…(Now) I believe who lives, who dies…has little to do with good or evil, but with effort…’ In this pulsating narrative at this point in the account, the reader will be shocked at the number of personal details about his life the writer dares to share. It must have taken a great deal of courage for such intimate disclosures. Consider the statement: ‘…given my childhood history of retarded, maladjusted and antisocial behavior…’ (pg. 92). But then a writer is only worth his salt to the extent he’s willing and unafraid and unashamed to be honest with his readers.

In the continuing effort to uncover who his father was in fact—‘not the man knocked down on the side of the road like a useless paper doll’ (pg. 17); not ‘the man lying (in a coffin) dressed for a wedding that would never take place’ (pg. 6); nor the man the writer laments he could never come close to emulating (pp. 35-39)—and to present that image to the reader, Reynolds devotes at least one entire, long chapter, ‘My Father Was A Beekeeper’ (pp. 188-205),to the one passion that his father loved above all his other occupations. At times one may complain that the ‘treatise’ entertains too much detail, goes on for too long; yet the father’s ‘lecture’ on the way of the bees is so packed with instructions for life that that criticism is soon withdrawn. By the author’s account, it appears that the older Reynolds applied the lessons learned from observing the bee colony toward the disciplining and upbringing of his brood: ‘My father always lectured us on helping each other, sticking by each other, protecting each other….’(pg. 201)—distinctive features of a thriving bee colony.

According to the author, the two episodes that best represent the man his father was are the brother’s—‘the one who’s a university professor’—eulogy and his own tribute poem at the funeral service. The images portray the man they both knew as opposed to all others of him in a state of rigor mortis on acold hospital slab, or in the mortuary prior to post mortem or lying still and helpless in a measured casket.

Despite the tone of sadness and utter loss that colours the first pages of the book, My Father Is No Longer There is decidedly not all doom and gloom, not exclusively death-focused. It offers glimpses of a typical ’60s Saint Lucian family’s path toward self-growth and social progress—industriousness, working the land or at a trade like tailoring, or for those able, a trip to the UK; it demonstrates that even in the most apparently perfect family there are issues of pain and sorrow, of sacrifice, of sweat and tears, of petty familial squabbles, of moments of celebration and of joy and laughter; to the reader less familiar with the backdrop against which the story is written, it gives a bird’s-eye view (almost cinematic) of large parts of the country as narrator drives home from the other extreme end of the country—deliberately unhurried—to confront the harsh reality of his father’s death (pp. 121-140 – ‘A Rendezvous With Death’).

Another thing: this is not fantasy, not fiction. Every bit is factual and historically verifiable—except where the writer strays (a rarity) and enters the realm of speculation.

In retrospect, Reynolds tells us ‘the possibility and hence fear of my parents dying had been a preoccupation since childhood’—no doubt brought on by the intense insecurity the infant Reynolds experienced due to the father’s absence and later the mother’s departure for England—however, ‘I can never get used to the notion…although ‘ Now I have a better appreciation…that fathers are irreplaceable…I cannot overcome the fact that my father is no longer there’. Hence, ‘Tell them I want my father back’ (pg. 186).

The side attractions notwithstanding, My Father Is No Longer There does succeed in the portrayal of the devastating impact of a father’s tragic, untimely death on a son. It does seem a bit strange though, doesn’t it, that given the writer’s acceptance of the imminence (pg.179) and immanence of death as attested to in his eulogistic poem—‘I know, Death,…/ both of us know that /life and Death are the same…’ (pg. 180)—he is unyielding to the fact of the loss?

The death of a loved one is nothing new, nothing unfamiliar. It’s how the story is told, and the other inside glimpses of a family in motion, that makes this one so compellingly readable.

Do I still hear someone asking, ‘But who was my father?’

Dr. Jolien Harmsen

Author of A History of St. Lucia, and Rum Justice

It took me a day or two before I made the time to sit down at my laptop, and begin reading Anderson Reynold’s latest book, My Father Is No Longer There.

Two hours later, I got out my phone and sent Anderson a WhatsApp message:

“Reading My Father. In one breath. I’m at page 63 now and he is gradually emerging, like a man walking towards me from a long distance. The book is a love ballad, Anderson. And the language so much more beautiful than anything of yours I have read before. Strong, supple and sensitive at once. I cried at one scene.”

The next day, I rushed around to get my work done, just to get home and back to the book. “I stayed up till midnight to read. Have just a little left now. Dreamed about it all night.”

The book that starts out as something I can only describe as a love ballad – odd as that word may sound when used to describe the relationship between a grown man and his deceased father – takes an unexpectedly desolate turn, just a few chapters later. Just when you’ve settled in to what appears to be the fabric of the memoir and the pattern of the story: a father tragically killed in old age, his adult son trying to come to grips with the trauma of that loss and, in doing so, weaving the narrative of his entire family’s history as 7th Day Adventists in Vieux Fort during the 1950s, 60s and 70s, the author suddenly shifts gears and the story takes an entirely more personal turn still.

The revelations that follow are unusual, not just in Caribbean literature, but in Caribbean social science as well. As a social historian myself, in all my reading on West Indian household labour strategies, I do not recall ever seeing anything that comes close to this testimony about the impact of (return) labour migration on the emotional well-being of the children left behind in the care of grandparents, aunts and others.

In Anderson’s hands, the trauma of his father’s death, one wet morning in June 2002, when a speeding driver lost control and hit him during his early morning walk, now becomes the touchstone for that much earlier trauma experienced when he was just a toddler: the temporary loss of his mother to the migrant stream that took tens of thousands of aspiring West Indian men and women to the United Kingdom, in the late 1950s and early ’60s.

Much has been written about the social, economic and political aspects of West Indian labour migration over the years, but the crushing emotional impact it -occasionally – must have had, remains virtually invisible in both academic works and Caribbean literature. From my own work on intergenerational relations in Vieux Fort since 1910, I can testify to the profound long-term impact of the quality of emotional relationships between children and their care-givers on those children’s future social, economic (financial) and educational development.

In Anderson’s own case, his family’s strong love and work ethics and, especially, his mother’s indomitable educational aspirations for her children did not save him from the long-term emotional trauma of that early childhood separation. But it did, however, help to keep him sufficiently focused to eventually be able to come through the emotional catharsis that followed, and out the other end of that long, dark tunnel of depression… and emerge as an accomplished author and analyst.

The two stories of trauma – his father’s death and his own early childhood anguish- thus become entangled in each other, are reflected in one another, creating contrast, depth, and perspective, like two hands playing the piano, like an image bouncing back between two mirrors, or like two birds struggling around each other in mid-air.

My Father is No Longer There is a biography and an autobiography, as well as an important addition to our understanding of the unwitting impact of West Indian migration on the psyche of the children involved.

The background to the story is that of a pastoral Caribbean childhood, a joy to read and a feast of recognition to anyone who is familiar with this slice of time and space, the shape and colour of it, the smell, the flavour, the colours, and the characters.

The language used to tell the story is very much Anderson’s own: verbal, direct, unadorned, its power derived sometimes from simple repetition, sometimes from raw dialect. What it lacks in finesse and grace, it makes up for in honesty, integrity and sheer forcefulness.

But to me, the overwhelming power of this book lies in the author’s inestimable courage, his willingness to explore, bare and share a deeply intimate side of himself to us, his readers. Because of this, reading My Father Is No Longer There is a privilege to be savoured, and one that ought to be treated with the respect it deserves.

John Robert Lee

Author of Pierrot

Among several works published by Saint Lucian writers in 2019 – poetry, novels, history, biographies, memoirs – one of the most unique and moving was My Father is no longer There by Anderson Reynolds.

Reynolds has published two novels: Death by fire (2001), The Stall keeper (2017), and one work of non-fiction, The Struggle for Survival (2003.) He co-edited the short-lived literary magazine The Jako, manages Jako Productions and has published his books and those of a number of Vieux Fort-based writers under his imprint Jako Books. An economist by training, he also manages musical groups out of Vieux Fort.

My Father Is No Longer There is a multi-layered text consisting of biography, autobiography, social history (covering farming, education, religion of rural Saint Lucia), memoir and confessional essay.

The 215-page volume is occasioned by the accidental death of his father. “On the wet morning of June 6, 2002, a car driven by a twenty-four-year-old motorist, spun out of control, ricocheted off another vehicle and plunged into my seventy-eight-year-old dad, who was on his regular morning walk alongside St. Jude’s Highway, on the outskirts of Vieux Fort, a town at the southernmost tip of St. Lucia.” The book and frank exposition which follow are rooted firmly in that opening sentence. The absurd accident, the Kafka-esque response of the insurance company, the coroner’s inquest, reaction of the family of the young driver, the writer’s bewilderment, lead into a searching examination of the meaning of his father’s life, his family experiences, their background in rural Saint Lucia, Reynolds’ becoming a writer.

The prose style and in particular the sections about his father, are excellent. A simple unadorned voice in which the strength of the first-person narrative, its emotional power (tempered by an objective searching out of what his family have experienced), provide a driving movement throughout the book that holds the reader’s interest.

Reynolds has given an incredibly detailed, closely observed account of his father’s life and the life of his family, including his own. Descriptions of farming (with a fascinating description of bee-keeping) school, religion provide a valuable record of the community he grew up in. In a chapter titled “A rendezvous with death,” he also probes, with a frank, confessional style, his reaction to his father’s sudden death, the old man now reduced to “a useless paper doll with dirt in his eyes, nose, and mouth.” His drive from Castries to Vieux Fort after he receives news of the accident, provides an opportunity to reflect on the island’s history, the immediate effect of sudden death of a parent and the way other people bring their own feelings to bear on the death of others.

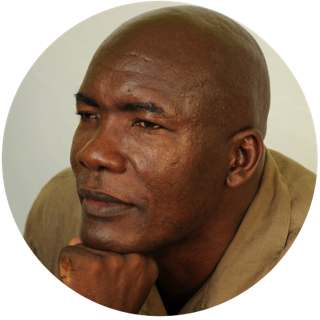

An illustrative addition adds poignancy to the memoir: a grey-scale photograph of his father is placed at the beginning of each chapter, and becomes clearer with each placing until at the end, the photo is the clearest. An interesting symbolic support which still leaves the urgent question,

“Who was my father” open, and possibly, unanswerable. How much can memoir or biography really reveal about a life study?

This may well be the best literary work of Anderson Reynolds. It adds to the rich literary heritage of Saint Lucia, and indeed the Caribbean, with our shared cultures and histories. Given our shut-in situation these days, I recommend we add this book to the Saint Lucian literature we are catching up on.